Functions, curves, and waves

The author discusses dominant images and concepts present in narratives about pandemic time.

Tatiana Bajuk Senčar

* Prispevek v slovenščini je objavljen pod naslovom Doživljanje pandemičnega časa. Povezava na koncu.

As I was doing some housework during lockdown, I came across some museum passes and receipts from a family day trip to Padua that we went on during the winter holidays. We had had exceptional luck that day, beautiful weather despite the forecast. Even though it was still February, the air felt almost spring-like. Like everyone else, I had been following the news about the virus, which was impossible to ignore, as the media daily covered its progression from China throughout Asia. While there had already been reports about isolated cases in Europe, it was not an issue that we thought of when making our plans – the virus was “elsewhere.”

It was only a few days after our trip, when news reports began tracing the trajectory of the virus in Italy from one of its centers in Lombardy towards the Veneto region, that this day became something else entirely in my mind. Our visit coincided with the dates of the first cases of the new Coronavirus in a town near Padua – and we became aware of the alarming proximity of the virus, no longer solely a subject of news but a potential factor in our daily lives. The days and weeks that followed were marked by heightened attention to all virus-related news as well as a sense of foreboding, waiting for the pandemic’s onset in Slovenia as one would an oncoming storm.

I have been struck by how trajectories, curves, lines, and waves became important tropes in the way we experience and talk about pandemic time. Speculations about whether or not the virus was present in Slovenia began weeks before the first case was officially detected. I can still picture in my mind’s eye how the news commentator in serious tones presented a map of the travels of the first persons in Slovenia diagnosed with the virus; they had taken ill abroad and brought the virus home with them. Routes, trajectories no longer represent the mobility and sociality of persons but also serve as pathways of viral progression, set in place days and weeks before a person even realizes they are ill.

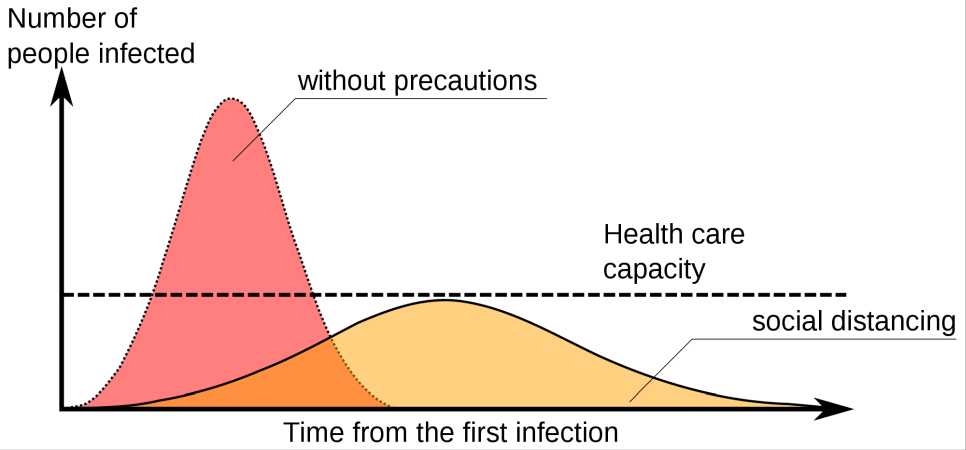

One of the news shows in the following days showcased a Slovenian scientist, who was describing how her institution was preparing for the potential arrival of the virus in Slovenia. She explained why they were so quick to adopt a plan by saying, “we all know what an exponential function is.” We have all come to recognize that steep upward curve, the one that marks the potentially devastating toll the virus can take given the high level of contagion that is one of its hallmarks. The moment the first case is detected, a country enters pandemic time and takes its place on a viral curve with a sense of mathematical inevitability, with countries being further or less along a given trajectory of contagion. When I would talk to friends and relatives worldwide, we would compare and contrast our situations in terms of this time: “we are one week ahead of you”, or “you are two weeks behind us.”

Experts, when questioned about the daily progression of the virus, were asked where we were on the viral curve – if we had reached its apex or not. “When” we are in terms of pandemic time is defined by “where” we are on the curve. This positioning is inextricably linked to the measures that transform daily life and practices as well as introduce a sense of out-of-time-ness resulting from the limited rhythms of the mundane.

As we progressed through pandemic time, along with many other countries battling the virus, it became clear that these viral curves could take many different trajectories, their level of steepness due to countless factors. I often find myself scrolling through the John Hopkins University COVID-19 website, comparing and contrasting the viral curves of different countries, which can serve as a tool for understanding “where” and “when” we are in pandemic time and space.

Of course, these curves are reductive, their clean lines based on numbers and statistics that reflect the fate of too many persons who have fallen ill, are hospitalized, or have lost their fight with the virus. These lines do not include those whom the virus has affected – directly and indirectly – but who do not fit into statistical categories. Despite this, viral lines and curves retain their narrative power.

These days, when it seems that we have succeeded in flattening the curve, talk about waves seems to become more prevalent, pointing to the potential resurgence of infection in the face of resuming certain daily practices. News bytes about viral states in countries across the world not only depict cases of the gradual suspension of quarantines but also, unfortunately, of new waves of viral infection.

I think that waves will become more central to talk about daily life in this phase of pandemic time, as we will be experiencing a gradual suspension of certain restrictions throughout this month. They will be useful not only in reference to the probability of viral resurgence, but they can also serve as a means of talking about its repercussions and effects on numerous dimensions of social life. Waves can be a tool for thinking beyond linear terms and for discussing and modifying livelihood strategies in ever-changing circumstances.

One Comment

Comments are closed.